Kenya: The Business Hub of East Africa

Kenya has emerged in recent years as one of the fastest growing economies in the world. Given the strategic importance its coastal city Mombasa plays and the favourable regional trade memberships, Kenya has often been referred to as the key economic and commercial hub of East Africa. Services sector being the key growth driver, improving transport infrastructure and ongoing pro-business reforms continue to underpin the notable economic development of the country and offer a wealth of opportunities for businesses and investors.

The Kenyan economy, largest in East Africa, has achieved considerable growth in recent years. The annual real GDP growth has averaged about 5.5% since the 2008 financial crisis, a rise that reflects the country’s continued economic stability and significant improvements in its business environment.

Agriculture remains the backbone of Kenya’s economy, accounting for about one-fifth of the country’s GDP, with coffee, tea and horticulture being its important export earners.

While manufacturing makes up just 10% of Kenya’s GDP, developing this sector remains an important strategy for Kenya, which the government sees it as a crucial engine for sustaining economic growth and development, job creation and poverty alleviation. Under Kenya’s Big Four National Economic Transformation Agenda, it seeks to increase the GDP contribution of the manufacturing sector to 15% by 2022, with particular emphasis on boosting sub-sectors such as agro-processing and textiles and clothing.

The services sector has been the key driver of Kenya’s economic growth, accounting for almost two-thirds of the growth in GDP over the last five years.[2] Tourism is one of Kenya’s most important industries and is a key foreign exchange earner. With its national parks, game reserves and other fine natural attractions, Kenya remains a natural tourism magnet which attracted almost two million visitors in 2018. Trading and financial services have also been important in driving the country’s economic development, supported by a relatively mature financial system and banking sector compared to other sub-Saharan African countries.

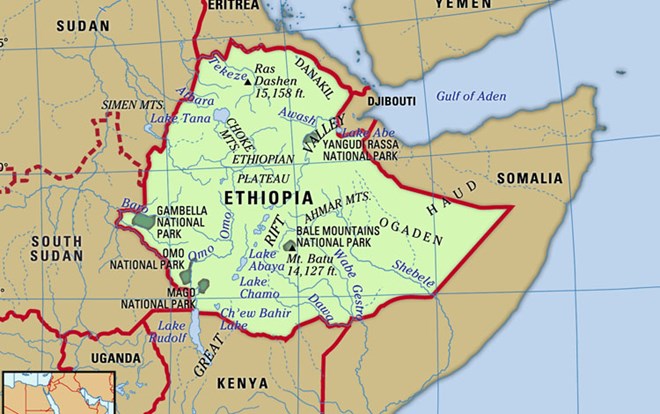

In contrast to much of the rest of the continent, Kenya’s diversified economy and long history of private sector development has made it the most attractive investment destination in the region. Kenya is the second largest foreign direct investment (FDI) recipients in East Africa, with its total FDI stock stood at approximately US$15 billion in 2019, trailing behind its neighbour Ethiopia. Investors are encouraged to keep an eye on the country’s fast-growing industries, particularly those in line with the Big Four Agenda – manufacturing, food security, housing and healthcare.

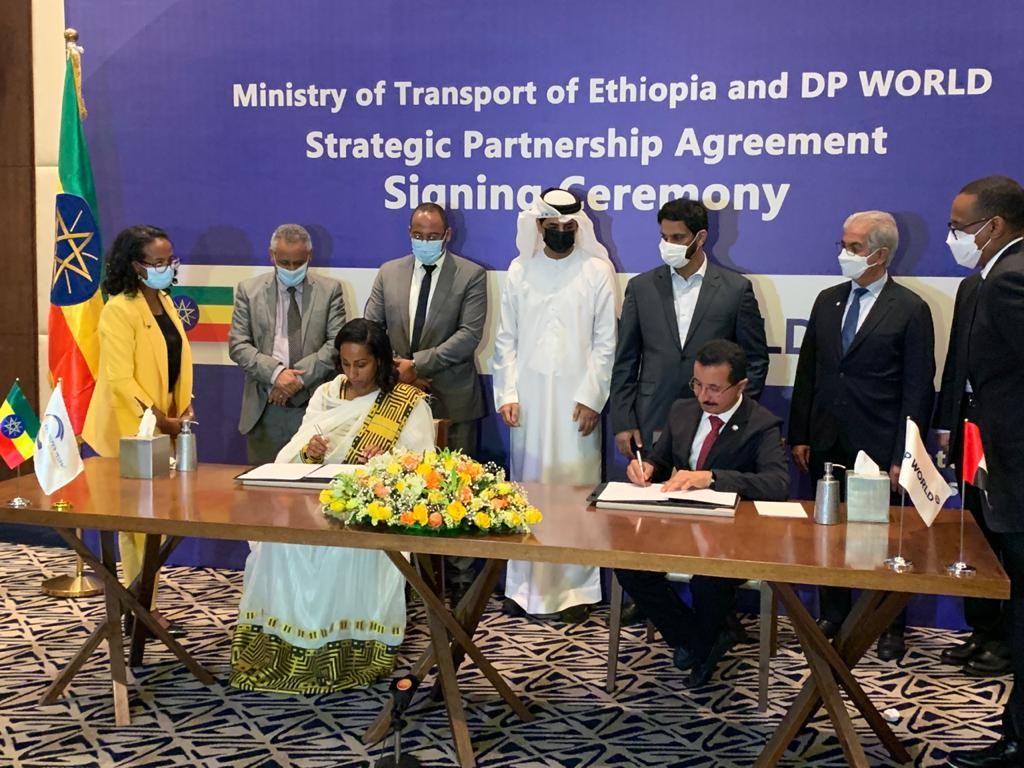

In recent years, Kenya has initiated a number of significant transport infrastructure projects intended to improve logistics efficiency and enhance its positioning as a regional trading and business hub. One notable example is the expansion work at the Port of Mombasa, the largest deep-water seaport in the East and Central African region.

Apart from serving the domestic market, the port also handles trade from landlocked neighbouring countries such as Uganda, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and South Sudan. In fact, Uganda is the biggest user of the Port of Mombasa, accounting for more than a quarter of the port’s cargo volume in 2020.

According to Kenya Ports Authority, Port of Mombasa is the fifth busiest port in Africa. In order to meet the demand of capacity increase – averaging at 10% annually over the past decade – the Kenyan government has rolled out the construction of a second container terminal at the port, the Kipeuv Container Terminal. Phase one of the Kipeuv Container Terminal was completed and became operational in 2016. Completion of the second phase, which is expected in 2022, will augment the capacity of the port by an additional one million TEUs.

To further facilitate trade and reduce traffic congestion between the Port of Mombasa and the country’s capital Nairobi, a standard gauge railway (SGR) was constructed and launched in 2017. Thanks to the SGR, traders are able to reduce as much as two-fifth of their freight costs, compared to transporting by road. The journey time has also been cut from 24 hours to a maximum of 8 hours.

The Mombasa-Nairobi SGR also offers passenger services, with two trains operating daily. Two years into its operation, the SGR has transported more than 4.4 million tons of cargo and offered services to 3 million passengers.

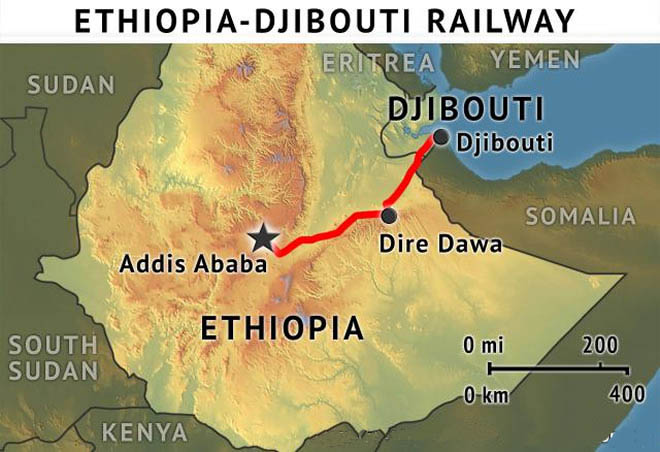

Regional integration is one driving force behind the continued investment in transport infrastructure in Kenya. The Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia Transport (LAPSSET) Corridor, a US$23billion multi-modal project, aims to provide better integration between Kenya, Ethiopia and South Sudan. It consists of six key projects, including a new port at Lamu in northern Kenya, inter-regional highways and standard gauge railway lines, an oil pipeline, new airports and the development of resort cities.

The Lamu Port, another deep seaport in Kenya, will mainly be a transhipping hub for cargo destined for ports such as Dar es Salaam in Tanzania and Maputo in Mozambique.

Kenya is identified as one of the rising stars of global trade, according to the Trade20 Index. Its membership of regional economic blocs, coupled with its infrastructure and ease of doing business improvements, is further consolidating its position as a gateway to African markets.

Kenya is a member of the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), the largest economic community in Africa, and the East African Community (EAC). Being part of these two regional economic blocs, which cover almost half of Africa’s population, provides Kenya with duty-free access to other member states while imposing a common external tariff on non-members.

In addition, Kenya has been at the forefront of the efforts to advance regional integration and form the largest free trade zone in the world – the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

While Kenya has shown a strong commitment to facilitate free trade within Africa, it has also forged numerous trade relationships with other countries. Kenya is a beneficiary of the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), which allows duty-free access to the US market for over 6,000 agricultural and non-agricultural products, such as garments and textiles. In fact, the US was the third largest market for Kenyan exports in 2018, behind only Uganda and Pakistan.

East African Community

Kenya is the only EAC member to have ratified the EAC-European Union Economic Partnership Agreement on quota restrictions and allows zero-duty entry into the EU of all EAC exports. Although the Agreement is currently stalled with Tanzania’s concern over its impact on the industrialisation in East Africa, Kenya still enjoys duty- and quota-free access to the EU market under the Market Access Regulation.

The wide market access provided under Kenya’s participation in numerous economic communities and agreements has offered a solid avenue for businesses looking to set up their bases in Africa. It is particularly attractive for manufacturers or exporters, who could take advantage to produce in Kenya given its quality transport infrastructure and competitive export procedures compared to its African peers, while enjoying the options to export to other African markets as well as mature markets such as the US and the EU.

As well as being a trading hub, Kenya also serves as East Africa’s diplomatic and business centre. Multinational corporations such as General Electric, Google and Visa have all established their regional headquarters in Nairobi. The city is also the African headquarters of international organisations, such as the World Bank and the United Nations.

Tech Hub of East Africa

Known as Africa’s Silicon Valley or “Silicon Savannah”, Kenya is embracing the ICT sector as a key enabler for future economic growth. Launched in 2006 and updated a decade later, the National ICT Policy aims to ensure the availability of accessible, reliable and affordable ICT services while promoting innovation within the sector. The updated Policy also addresses a number of newer issues, such as cybersecurity, e-government and knowledge economy.

The enabling policy and legal environment have seen the development of many innovations, including M-Pesa, a mobile payment and transfer system launched in 2007 by the leading Kenyan telecom operator Safaricom. M-Pesa has proved that even the most basic mobile phone can enable users to send, receive and store money. The application of M-Pesa has spread quickly and it now has over 37 million active customers across seven countries in Africa.

Kenya is also home to more than 200 tech start-ups, as well as the regional headquarters of multinationals in the ICT sector such as IBM, Intel and Google. In Nairobi, Microsoft has opened an Africa development centre and Cisco, a supplier of networking equipment, has also set up an innovation hub.

Boasting one of the fastest internet speeds in the region given its undersea fibre-optic cables, Kenya is now characterised as a truly connected landscape. That, combined with the growing population with access to technology and increasing support from international investors, the Kenyan tech ecosystem offers an attractive space for investment and innovation.

Businesses operating in Kenya stand to benefit from a host of incentives. The Kenyan government provides the right for foreign and domestic private entities to establish and own business enterprises. In an effort to encourage foreign investment, Kenya repealed regulations in 2015 that imposed a 75% foreign ownership limitation for firms listed on the Nairobi Securities Exchange, allowing such firms now to be 100% foreign-owned.

Food Processing

Besides the apparel sector, opportunities exist in the country’s agribusiness. Kenya is reputed for its cultivation of tea, coffee, grains and fruits. It is the largest exporter of horticulture in East Africa and the third largest tea exporter globally. Kenya also boasts of large herds of dairy cows which provide fresh milk for processing into pasteurised milk and other dairy products such as yoghurt and ice cream.

Located near the Indian Ocean, this is also growth potential for Kenya’s aquaculture industry. In fact, the country has been exporting fish and seafood to international markets such as the EU, although aquaculture exports only accounted for less than 1% of its total exports. As the raw materials for food processing businesses are readily available and can be sourced locally, there is potential to expand value-addition production and food processing in Kenya.

Not surprisingly, fishery and horticulture products are major exports from Kenya. As the world demand for Kenyan fresh food produce increases, there are untapped opportunities which can be matched with the expertise from internatonal companies with the aim of developing the fishery and agribusiness value chains in Kenya, particularly in cold storage facilities and refrigerated transportation for perishable food products, as well as quality packaging for food produce.

To capture manufacturing and processing opportunities, one could consider Kenya’s export processing zones (EPZs) and special economic zones (SEZs). Both EPZs and SEZs offer a range of incentives to support low-cost and smooth operations and encourage foreign investment. These include measures such as a ten-year corporate tax holiday and exemption from duty and VAT.

Investors should note that the major difference between EPZs and SEZs is that EPZs aim to support export-oriented businesses, and therefore companies are required to export at least 80% of their output outside Kenya as well as the East African Community (EAC) region in order to operate in an EPZ. EPZs also target companies in particular sectors, such as food processing, textile and apparels, leather and commercial crafts and pharmaceutical and medical products. In 2018, there were 72 EPZs in Kenya, of which 67 were privately owned and operated.

The wide market access which Kenya has achieved through its participation in numerous economic communities and agreements offers a solid avenue for manufacturers to produce their goods in Kenya, coupled with its quality transport infrastructure and competitive export procedures compared to its African peers. Despite Kenya’s manufacturing and export potential, businesses should take note of the operational challenges they may face.

The cost of labour in Kenya is uncompetitive as it has the highest monthly minimum wage in the region, which could be unfavourable for labour-intensive industries.

Furthermore, import procedures are relatively lengthy, which may result in increased costs and delays for inbound freights.

Risks of Doing Business in Kenya

As a note of caution, it is prudent here to point out that the Kenyan economy still remains vulnerable to volatility in external financial markets. As 2020 has shown, a substantial downturn in China, which is a major financier of Kenyan infrastructure projects, poses significant downside risks for investment into the country.

In addition, Kenya’s current account deficit will widen due to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 as tourism receipts and foreign remittances collapse due to the global slowdown. The shilling is also susceptible to periods of high volatility that can feed through into inflation and undermine investor sentiment. That said, Kenya dominates the East African Community trade bloc and serves as the region’s logistics hub, which will allow it to leverage the region’s rising prospects in the coming years.