Djibouti Port: Trade and Logistic Hub for Africa

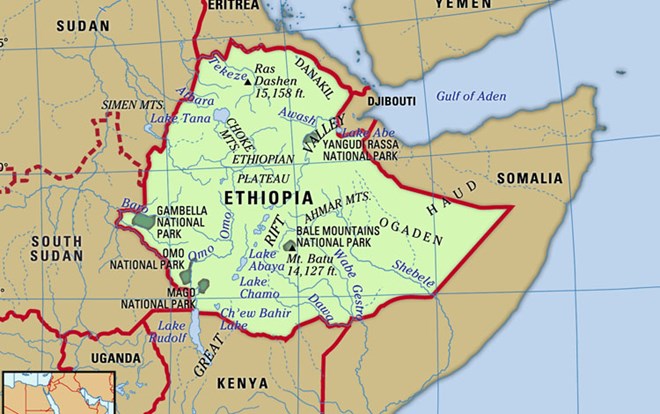

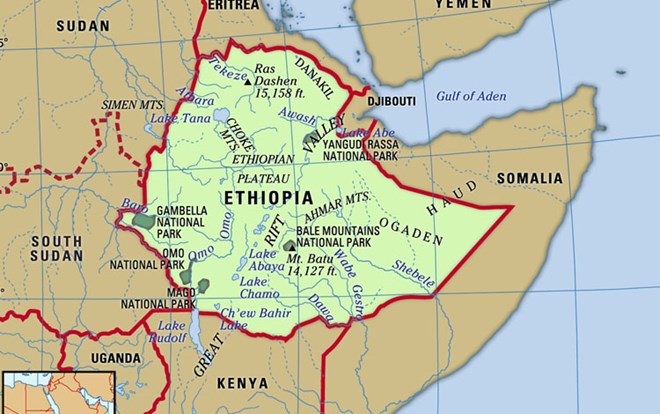

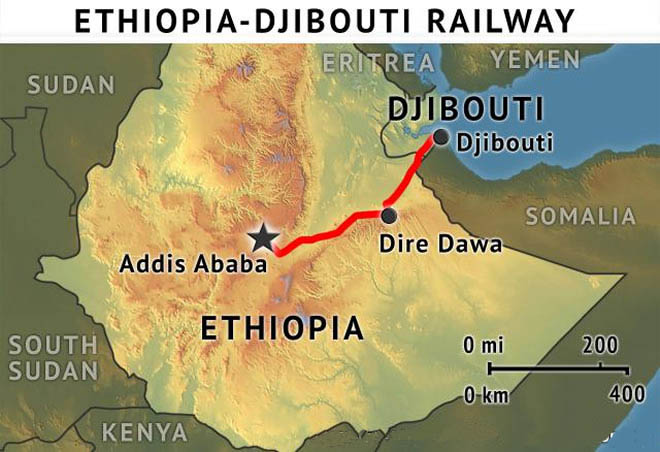

More than a century ago, when the old Port of Djibouti was built by the French colonisers, it was connected with a railway that linked Addis Ababa to Djibouti City. Given the size differences of the two countries – today Ethiopia’s population is more than 100 million, while Djibouti’s is less than 1 million – the port was never about trade with Djibouti, but trade with Ethiopia. It is no coincidence that today, the new Doraleh Container Terminal is the end of the line for the new Chinese-built Addis-Djibouti standard gauge railway.

Djibouti had little going for it when it became independent in 1977, but by exploiting its geographic position and putting into place well thought-out policies, it has developed into a global trading centre.

Djibouti’s position as the main entrepôt for Ethiopia was cemented in 2017 when the new Ethiopia-Djibouti Railway was completed. It replaced the ageing colonial-era line and reduced freight transport times between Addis Ababa and the Port of Djibouti from 50 hours to 12 hours.

The Tadjourah-Balho-Mekele road, a highway connecting Djibouti and Ethiopia was recently inaugurated. The inauguration was attended by Djibouti president, Ismaïl Omar Guelleh, Ethiopian minister of transport and other dignitaries.

The 120km road is set to connect the new Tadjourah port of Djibouti, dubbed a third corridor to the small town of Balho the city of Mekelle the capital city of Tigrai, Ethiopia. The Tadjoura Port has been built to mainly focus on general cargo, such as livestock, sesame, frankincense, fertilizers and grain.

Historically, one of Djibouti’s strategic advantages has been its stability. In an inherently unstable part of the world – its other neighbours include Eritrea, Somalia and Yemen – Djibouti represents a relatively low-risk investment destination. But Somaliland is providing competition on this front.

If trade from Ethiopia dries up, ships will no longer be queuing at sea for their turn to dock at these ports. This is significant because there are two separate situations that threaten the trading relationship between Ethiopia and Djibouti. The first is the brewing political crisis in Ethiopia.

Djibouti Port: Promoting Trade With Ethiopia

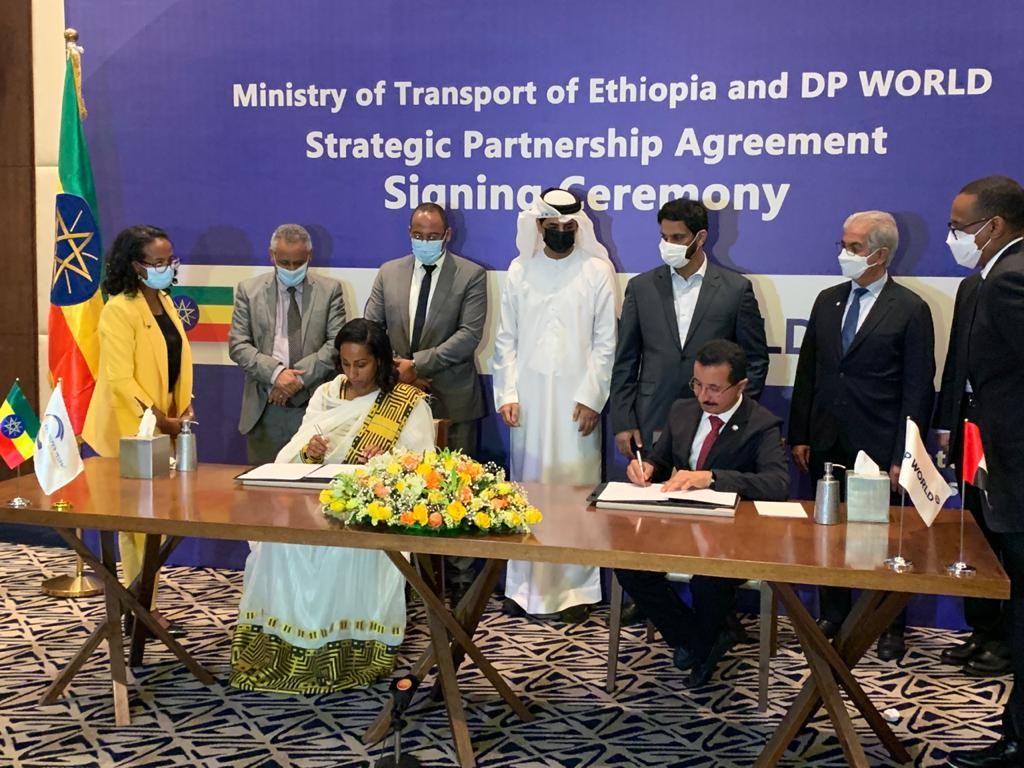

The government of Djibouti is determined to strengthen the country’s position as the premier port site in the Horn of Africa. Ethiopia is seeking to diversify its range of port options and has signed deals to use Port Sudan in eastern Sudan and the emerging port of Lamu in Kenya.

The World Bank estimates that Djibouti’s GDP grew by 7.2% in 2019 and predicted growth of 7.5% in 2020 and 8% for the 2021-23 period. These figures are likely to be downgraded as a result of the coronavirus crisis but the country’s long-term economic prospects look very sound. The economic base is already beginning to widen with the emergence of construction materials and food processing sectors.

Under Vision 2035, the government aims to create a more diverse economy by developing a digital technology hub, promoting light manufacturing export processing zones and improving national infrastructure, as the port and logistics sector continues to grow. Plans have also been drawn up to attract investment in financial services, tourism and renewable energy. Concrete targets have been set, including creating more than 200,000 jobs and tripling per capita income by 2035.

Tadjourah-Balho-Mekele

The US $156m road project was financed by the Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development (KDEF). The new highway will go through the Djiboutian border town of Balho intercepting the road to the port of Assab in Eritrea which used to connect Ethiopia to the sea and will go through Afar to Mikelle the capital city of Tigrai.

In 2017 Djibouti opens a new port at Tadjouran in North-Central Djibouti, which is equipped with cutting edge facilities, including a potash handling system with a capacity of 2,000 tons per hour.

The port is developed in conjunction with other major infrastructure works in the region, including the North Tadjourah-Balho corridor highway, and the proposed expansion of Djibouti’s railway system with a new northern corridor railway.

Port of Tadjourah, in the north of the country, is the closest outlet for Ethiopia’s Afar and Tigrai regions, where a number of companies are developing potash mines.

Tigrai Online has received relevant information that the extremist Amhara groups were actively working with the help of the Egyptian government to undermine the completion of the Tadjourah-Balho-Mekele road. The enemies of Tigrai desperately tried to sabotage the construction of the new highway to cut off Tigrai from the sea and limit it to be only through Addis Ababa-Woldiya-Mekelle and then they turned around and closed the federal highway connecting Addis Ababa and Mekelle.

Highway connecting Djibouti and Ethiopia

The construction of the highway will help relieve the congestion of commercial traffic between the port of Djibouti and Ethiopia. The new road will also cut down the travel time for trucks going from Djibouti to Afar and Tigrai states substantially. Since the new road doesn’t go through the Amhara regional state the difficulty, robbery, road blockage, and other illegal activities against any transportation systems will be eliminated.

The brand new Tadjoura Port is built to mainly focus on general cargo, for example livestock, sesame, frankincense, fertilizers and grain.

Around 97pc of Ethiopia’s import-export cargo has been coming through Djibouti's ports since the 1990s. The rest are shipped through Port Sudan and Berbera, respectively. Until last year, imported freight of Ethiopia stood at 13.5 million tonnes, while exports reached more than 1.8 million tonnes a year.

Ethiopia had been using Assab and Massawa ports in Eritrea, both of which are close to the northern parts of the country before the late 1990s until diplomatic relations between the countries deteriorated.

Trade with Ethiopia

The fast-growing Ethiopian economy has accelerated traffic through the Port of Djibouti, with the volume of containers handled rising from 176,453 in 2002 to 854,851 in 2014, according to figures by Djibouti Ports and Free Zones Authority (Autorité des Ports et Zones Franches Djibouti, APZFD). Figures also show an average of 1500 transport trucks crossing the border daily between Ethiopia and Djibouti, with this expected to climb to as many as 8000 trucks by 2020.

Currently, the shipping cost of bringing a twenty-foot equivalent unit from Shanghai into the Port of Djibouti is around $600 and takes 14 days, with an additional $750 and two days needed to take the container all the way into Addis Ababa in Ethiopia, according to figures by the APZFD. However, freedom in determining the price for freight forwarding in Djibouti led to a discrepancy in prices, with prices charged for Customs and port procedures varying from between DJF18,000 ($100) to DJF40,000 ($225), according to figures by the APZFD. To prevent price variability from impacting the competitiveness of the Djibouti-Ethiopia corridor, the government established fixed prices for these operations in 2015, with the new regulations enforced from January 2016.

Road congestion has been a major problem when linking cargo transport between Djibouti and Ethiopia but work is afoot to shift traffic off the road, and onto a recently rebuilt railway line. The 753-km Chinese-financed railway link will be able to transport up to 3500 tonnes per voyage between the countries – seven times the maximum capacity of the previous line – and cut travelling times to around ten hours, from the current average of two days it takes trucks. Speaking to media in 2015, Getachew Betru, chief executive of state-owned Ethiopian Railways, described the project as a “game changer,” adding, “It will be one of the most vibrant economic corridors in the world.”

Djiboutian officials hope the railway will eventually be extended to South Sudan, the Central African Republic and Cameroon, connecting the Red Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. Longer term, officials hope to build on the country’s geographical position, abutting markets in the Middle East, North Africa and East Africa, along with its transport links by developing special economic zones, where foreign companies will be able to assemble goods.

New Pipeline

Another project set to ease overall cargo transport will be the construction of a 550-km pipeline between Djibouti and central Ethiopia. The $1.55bn project will be used to ship refined petroleum products, which have been typically transported using tanker trucks. The new infrastructure will have the capacity to move 240,000 fuel barrels per day. “The energy pipeline is likely to improve road congestion and will create more room for logistics companies,” Reuben Ahronee, director-general at Massida Group, a local logistics operator, told OBG.

Djibouti is a key transhipment centre and the main seaport for Ethiopian international trade since it is strategically located near the busiest sea routes in the world, controlling access to Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. Upon completion the highway is expected to relieve the congestion of commercial traffic between the port of Djibouti and Ethiopia.

The new road will also cut down the travel time for trucks going from Djibouti to Afar and Tigrai states substantially. Moreover, since the new road doesn’t go through the Amhara regional state the difficulty, robbery, road blockage, and other illegal activities against any transportation systems will be eliminated.