Africa: Ripe for Business: Export to Africa and Reap the Benefits

Currently, 6 of the world’s 10 fastest growing economies are in Africa, and the ease of doing business in Africa is improving to the extent that a good number of countries (including South Africa, Ghana, Mauritius and Tunisia) now outperform China, India, Brazil and Russia. In addition, FDI inflows to Africa have demonstrated year-to-year growth since 2010 and now amount to US$ 50 billion.

The key reasons behind this growth surge included government action to end armed conflicts, improve macroeconomic conditions, and undertake microeconomic reforms to create a better business climate. To start, several African countries halted their deadly hostilities, creating the political stability necessary to restart economic growth. Next, Africa’s economies grew healthier as governments reduced the average inflation rate from 22 per cent in the 1990s to 8 per cent after 2000. They trimmed their foreign debt by one-quarter and shrunk their budget deficits by two-thirds.

The key reasons behind this growth surge included government action to end armed conflicts, improve macroeconomic conditions, and undertake microeconomic reforms to create a better business climate. To start, several African countries halted their deadly hostilities, creating the political stability necessary to restart economic growth. Next, Africa’s economies grew healthier as governments reduced the average inflation rate from 22 per cent in the 1990s to 8 per cent after 2000. They trimmed their foreign debt by one-quarter and shrunk their budget deficits by two-thirds.

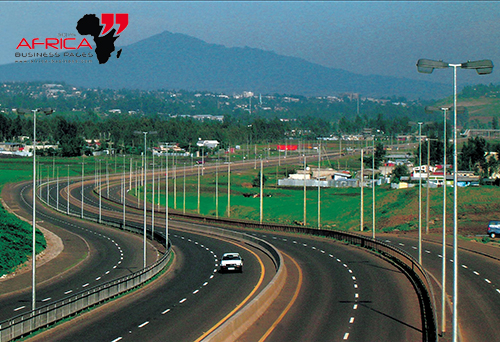

Finally, African governments increasingly adopted policies to energize markets. They privatised state-owned enterprises, increased the openness of trade, lowered corporate taxes, strengthened regulatory and legal systems, and provided critical physical and social infrastructure.

Nigeria privatized more than 116 enterprises between 1999 and 2006, for example, and Morocco and Egypt struck free-trade agreements with major export partners. Although the policies of many governments have a long way to go, these important first steps enabled a private business sector to emerge.

Together, such structural changes helped fuel an African productivity revolution by helping companies to achieve greater economies of scale, increase investment, and become more competitive. After declining through the 1980s and 1990s, the continent’s productivity started growing again in 2000, averaging 2.7 percent since that year. These productivity gains occurred across countries and sectors.

This growth acceleration has started to improve conditions for Africa’s people by reducing the poverty rate. But several measures of health and education have not improved as fast. To lift living standards more broadly, the continent must sustain or increase its recent pace of economic growth.

To be sure, Africa has benefited from the surge in commodity prices over the past decade. Oil rose from less than $20 a barrel in 1999 to more than $145 in 2008. Prices for minerals, grain, and other raw materials also soared on rising global demand.

Political change in Africa is rapidly happening in unexpected pockets. Observers are actively monitoring situations in certain countries, in particular South Africa, Ethiopia, and Zimbabwe, with an excitement for future socio-political change that could follow these headwinds.

Yet all consideration of the current political movements suggest that the imagined economic change is not necessarily an easy sequel to the political prologue. Political change is also sweeping across the African contient:

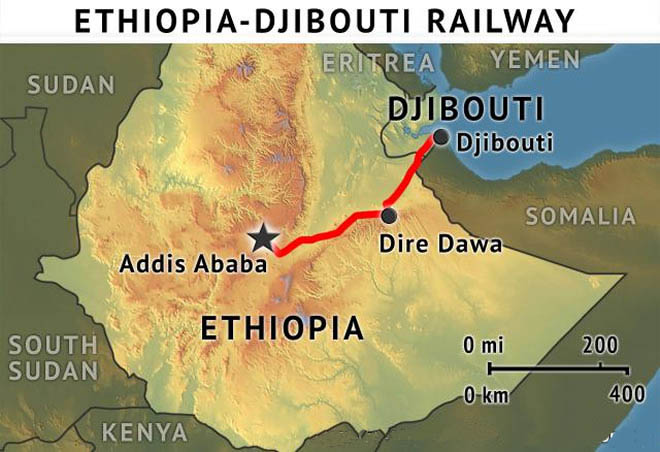

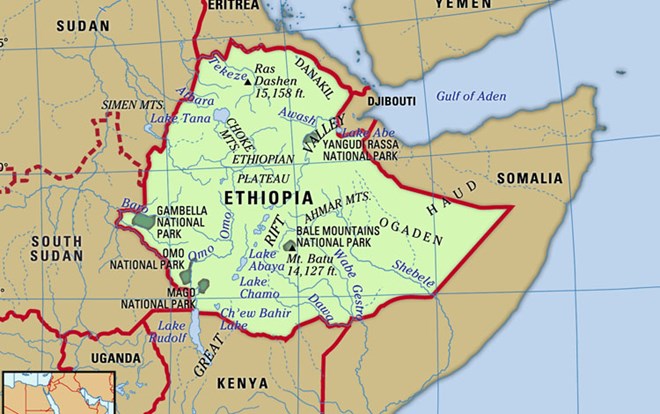

Ethiopia

The unexpected (or expected, depending on who you ask) resignation of Ethiopian Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn, in theory, paves the way for change. But many insiders are not exactly sure what path will be chosen by the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front.

Faced with ongoing demonstrations that began sporadically in 2015, the ruling party has two options in front of it:

- Choose someone open to allowing increased political freedom or

- Appoint a party hardliner to shut down the dissent.

For many political analysts, the arrival of Desalegn’s resignation day is an odd juxtaposition with the rising economic prowess of the country. Ethiopia, as it goes, always craftily kept political freedom and economic growth in two separate buckets of discussion, especially as the growth justified the political environment in which it excelled.

For many political analysts, the arrival of Desalegn’s resignation day is an odd juxtaposition with the rising economic prowess of the country. Ethiopia, as it goes, always craftily kept political freedom and economic growth in two separate buckets of discussion, especially as the growth justified the political environment in which it excelled.

But the death of the pervasive and endearing prime minister Meles Zenawi in 2012 opened the door for a discussion on politics in conjunction with economic transition, theoretically blurring the line that separated the two subjects in public discourse. The economics of the country could possibly have to account for its internal politics.

Yields on Ethiopia’s $1 billion 2024 Eurobonds fell a few basis points after the government announced a state of emergency following the prime minister’s resignation. That drop was not significant enough to stir major concern amongst investors in the country.

But investors will watch closely to see how the next few months play out. Two things are increasingly truer today than yesterday: (1) Ethiopians think protests can affect political change and the stance of the country’s political leaders, and (2) markets and investors have punished other countries for instability (ask Kenya in late 2017 and South Africa for the last two years).

Zimbabwe

The death of Zimbabwe opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai quickly followed the exit of former President Robert Mugabe. With no clear leader to fill the power vacuum in the opposing Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) party, the ruling ZANU-PF may face little opposition in a presidential election expected before July this year.

Tsvangirai won, at least, in the first round of the vote in 2008, but eventually lost a disputed election to Mugabe and later formed a unity government with him. Some opposition leaders are suggesting that the death of Tsvangirai may encourage President Emmerson Mnangagwa to ensure the Zimbabwe election stays on track with timing.

That positive, in the eyes of political critics, is not too positive if a true debate on the economy and the general direction of Zimbabwe cannot be had without a face or voice to put opposite President Mnangagwe.

The reuniting of Tsvangirai last year with his former allies, Welshman Ncube and Tendai Biti, who both left Tsvangirai’s wing of the party, to run together in the 2019 elections was a boost to the opposition’s spirits in the midst of flailing motivation and energy in the anti-Mugabe camp.

Yet now the question becomes whether the former allies can push forward in Tsvangirai’s memory and Mugabe’s absence. No one truly knows where the allegiances may fall. Some observers suggest that ZANU-PF is not a tight-knit as advertised. Even if true, ZANU-PF has proven its ability to win national elections.

Regardless, the economics in the country require change. Zimbabweans need infrastructure, an economic rebound, and jobs among other things.

But who has the new ideas and energy in 2018 to endure a long process in rejuvenating the economic spirits of businesses and locals?

Investors and markets – excited to have a serious discussion on Zimbabwe again – want to reward the country for political change. Yet the question may still be whether Zimbabwe cares about what outsiders are saying or what the market is selling it.

South Africa

The rise to the presidency for Cyril Ramaphosa in the immediate aftermath of the resignation from South African President Jacob Zuma spells opportunity for the challenged country.

Investors, markets, and pundits alike have punished Africa’s most developed economy for Zuma’s leadership and rule. It only follows that the stark opposite leader – admired in the business community for his successes and once pursued by the beloved Nelson Mandela to be his deputy president – should spell relief for investors and potentially have a Trump-esque bump on markets in the early days.

Yet the ‘dawn of a new day’ in South Africa may require more than a simple change of leadership.

Yet the ‘dawn of a new day’ in South Africa may require more than a simple change of leadership.

The South African mining sector requires wage and ownership changes as well as tax changes to spur more investment and strengthen a buried gem (no pun intended) in the country.

The economy requires a solution to energy troubles. The state-owned power company Eskom remains a trouble spot for the country with regards to its poor balance sheet performance. And the country needs jobs to combat unemployment and boost consumer spending as nearly every consumer and retail-based related sub-sector complains that South Africans cannot afford to spend despite their usual appetite for doing so.

Beyond the economics and the politics, President Ramaphosa will have to battle pockets of nationalism within the country that want to restrict land rights, fight back against privatization, and avoid the dirty fights to reform certain government institutions, such as the South African Revenue Service.

At the end of the day, political change and the arrival of President Ramaphosa may be a breath of fresh air, but the ruling party cannot inhale too long with too much on its plate to do and with an impending general election. A few early reforms may be the difference between winning and losing for the ruling ANC in early 2019.

The message to any company or investor still not in Africa is that today is the day that business in Africa is made and it might already be too late tomorrow. Africa is the now, no longer the future.

Any CEO who has not presented his or her board of directors with their Africa strategy needs to get to work on such a plan and implement the plan as soon as possible in order to reap the benefits by gaining first entry into the emerging markets in Africa.

The Africa train has already left the station. You are either on it or you risk becoming irrelevant.

.png)